Apostolic Identity and the Words of Scripture: Part 2

The Same Old Attack

Introduction and Review

Attacks have been made stating that Luke summarized or crafted the ‘speeches’ in Acts to match his own theological agenda. The ‘speeches’ (sermons), were not exactly what the speakers said, but supposedly what Luke wanted to convey to his audience.

Critics make blanket statements to argue that all ancient historians practiced the same methods, therefore, Luke would have done the same. Specifically, the concocting of speeches for rhetorical purposes. However, in Part 1 of this series, we analyzed how ancient authors wrote history and observed that not all historians were equal. Some wrote as playwrights for entertainment but others wrote with high concern for accuracy. Thus, the generalized grouping of historians is a flawed classification.

Furthermore, it was noted that Jesus and the NT authors believed that the very letters and words of Scripture would be preserved. I concluded with, “If we lose the words of Scripture then we lose the events, and finally, revelation itself. As Apostolics, we should hold the Apostles and their testimony in the highest regard. If we do not then everything we stand upon will crumble.” At that point, our identity and our mission will cease to be meaningful to the world. Close the church doors, we do not even have a Bible anymore.

Part 2 requires us to analyze Luke and the Biblical evidence more closely. Although Luke and Acts are in focus, the other three Gospel accounts would be impacted as well, because all the sermons rely on firsthand witnesses. If we cannot trust Luke’s record of Peter-Paul’s sermons, how could we trust the sermons of Jesus?

Luke as a Historian

Because of postmodernism and the culture of the day, it is popular to assert that authors always have a bias or an agenda behind everything they write. When this concept is applied to the Bible it is called narrative criticism. This position would deny Luke wrote Acts as a historian, and deny and/or diminish the working of the Spirit upon Luke as an author. Rather, Luke wrote ‘narrative history’ with a desire to use the stories to create a propaganda work. Some narrative assertions sound like this, ‘Luke re-created the speeches, not out of thin air, but summarized them to match his own theological purposes.’ Meaning, the sermons may not be totally accurate, but they were crafted by Luke to portray certain ideas to his readers. Some would refuse to use the word propaganda but that is what Acts becomes with narrative criticism.

F. F. Bruce stated, in regard to Luke, that if an author’s trustworthiness “is vindicated in points where he can be checked, we should not assume that he is less trustworthy where we cannot test his accuracy.”

Sir William M. Ramsay (1851-1939) was a skeptic who set out to disprove Luke’s writings. Considered an expert in multiple historical fields, he made several journeys throughout Biblical lands and uncovered numerous archaeological artifacts. The evidence of Luke’s accuracy was so overwhelming that Ramsay was thoroughly persuaded of the NT’s reliability.

Ramsay stated,

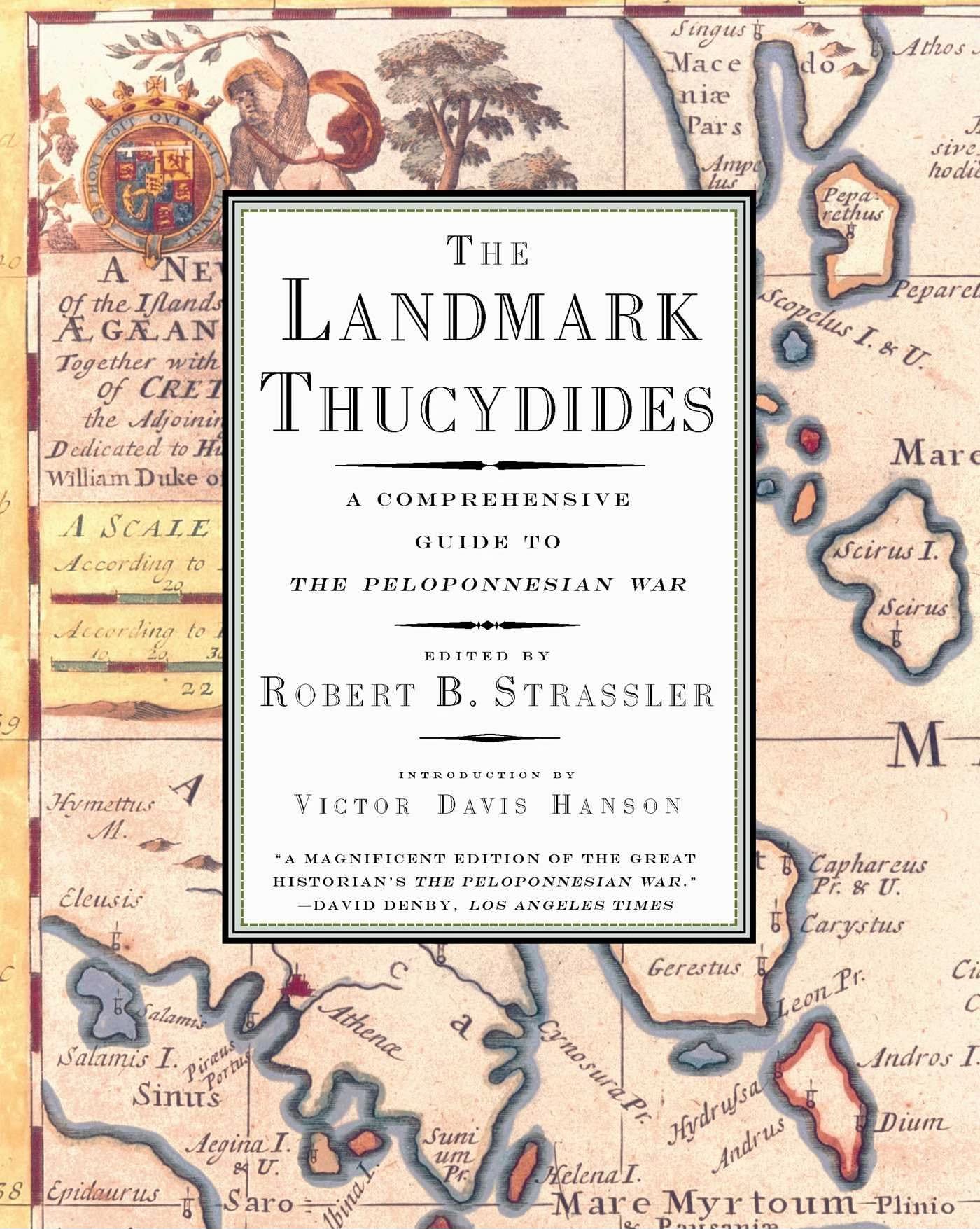

“The author of Acts is not to be regarded as the author of historical romance, legend, or third- or second-rate history. Rather he is the writer of an historical work of the highest order, a work to be compared with that of Thucydides, the greatest of the Greek historians” (St. Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen, 2-3)

In contrast to the liberal comparison mentioned in Part 1, this comparison to Thucydides is a compliment. Here are a few points to observe regarding Luke as a high-class historian…

Looking at the missionary journeys alone (Acts 13-28), there are approximately 84 verified facts. These facts include geography, local politics, local customs, leaders, and more. The exact precision of these details relates to us that Luke was present at the event(s), or spoke to someone who was.

Stephen’s sermon (Acts 7) grants us insight into Luke’s accuracy. Luke preserved Stephen’s sermon, which follows the progression of multiple OT texts. We can note that Stephen’s sermon is faithful to the OT, which obviously means that Luke was faithful in his record-keeping. It follows that Luke accurately preserved an event which he was not present to witness, and very well could have done so for other sermons in Acts.

One may argue that Luke fashioned the sermon merely from having the OT stories in front of him, not from what Stephen truly said.

We know that Paul was an eyewitness to Stephen’s trial and death and Paul has been acknowledged to be the Apostolic authority behind Luke. Therefore, based on Paul’s common practice of calling out falsehood, we would expect Paul to correct any of Luke’s errors. Instead, we see the opposite, Paul endorsed Luke’s writings and called them Scripture—see Luke 10:7 & 1 Tim. 5:18.

This issue comes down to what presuppositions are being held: does one hold a high view of inspiration and preservation or a low view? The presupposition will determine how the sermons are understood, as the presupposition will inform the data available.

How could Luke gain information he was not present to see himself? Luke did his research (Luke 1 & Acts 1) and he was an eyewitness for many events (cf. the ‘we’ passages) in Acts. Furthermore, he had access to the Apostles, especially Paul.

It seems that Luke could have spoken with the Apostles themselves, and the Holy Ghost moved on him to faithfully write down what the Apostles relayed to him.

Ramsay further stated,

Our hypothesis is that Acts was written by a great historian, a writer who set himself to record the facts as they occurred, a strong partisan indeed, but raised above partiality by his perfect confidence that he had only to describe the facts as they occurred, in order to make the truth of Christianity and the honour of Paul apparent....

Luke was the author of history, events as they occurred, not writing for his own agenda.

Luke and the Witnesses

Everything we can verify in the Gospels and Acts has been shown to be truthful, therefore, we have no logical reason to doubt the sermons. As stated before but needs to be reiterated, Luke was in a position to speak directly with eyewitnesses or be a firsthand witness himself (cf. Luke 2:19—Luke may have talked to Mary about this event!) This is different than, say, Thucydides. The Greek historian said he was preserving events that spanned multiple years with a wide geography. Thucydides admits he was not always able to gain direct testimonies (some sources may have been secondhand), so again, we need to be careful when comparing Luke with other ancient historians.

Furthermore, the firsthand accounts of Jesus were numerous (1 Cor. 15), many of which had seen Jesus resurrected and were still alive in the mid-50s AD. This is significant considering Luke finished writing Acts around AD 62. Thus, Luke may have had one or two decades of time to interact with ‘first generation’ Christians before writing his books.

An important note, and perhaps the most worthy of attention, comes from John 14:26.

But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in my name, he shall teach you all things, and bring all things to your remembrance, whatsoever I have said unto you.

Jesus said that the Apostles would have perfect and total recall of memory for what Jesus had taught. Supernatural memory! This would lead us to understand Jesus’ sermons as faithful word-for-word accounts, and if Luke’s Gospel correctly preserved the words of Jesus, could we believe the Apostle’s words to be preserved as well?

Therefore, if we have evidence of word-for-word accounts in history (again see Part 1), and the Holy Ghost’s inspiration upon NT authors, then doubting Luke’s sermons seems unnecessary.

Sermon Length

One author argues that ‘because ancient speeches were always long, and sermons in Acts are short, it follows that Luke summarized the sermons.’ However, this is faulty reasoning. We know that some sermons were long (Acts 20:7), but Luke gives us clues when he is not telling us every word that was spoken. For example, in Acts 2:40, Luke tells us directly that he has given the main idea of how Peter concluded his sermon but without every sentence. Seeing this indicator, how are we to take the first part of Peter’s sermon? We should take it as it is written, ‘then Peter said’ is actually what Peter said.

Also, we should be conscious that a book like Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War is nearly 200,000 words long, while Acts is under 20,000. If you read Thucydides, some of the speeches go on for multiple pages and are followed by additional speeches by different speakers. Luke is writing a letter that is much shorter in general, therefore, to highlight that the speeches (sermons) are shorter does not give the entire picture.

The goals of both authors are slightly different, as Thucydides is writing a political document tracing one of the largest conflicts in ancient Greece, and covers a lot of ground showing the escalation and the multi-decade war itself. Luke covers 30 years of history in less than 20,000 words, he is more precise in focus and does not give us the grand story of each disciple, each convert, or miracle. Acts is a brief but thoroughly accurate history of the early church in the form of a letter.

Conclusion

To be ‘Apostolic’ means we follow the doctrines and practices of the Apostles. They held to the very letters and words of Scripture as God’s revelation to humanity. We must have reliable revelation if the revelation is to be any use to us. If we cannot trust the words, then what we ‘practice’ from those accounts becomes shaky. Attacking the words of God has occurred from the beginning (Gen. 3) and will continue until He returns. Apostolics today must define their position and hold fast to every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.

Why was Jesus Baptized?

In 2022, I graduated with my Masters in Biblical Studies from Liberty University— Rawlings School of Divinity. My final project was a 60-page paper, which I completed over a 5-month span. I asked Dr.…

Two blogs that also defend Apostolic Doctrine,