The Fullness of Time: Before the Manger

Galatians 4:4-5 says,

4 But when the fulness of the time was come, God sent forth his Son, made of a woman, made under the law,

5 To redeem them that were under the law, that we might receive the adoption of sons.

Paul wrote that in the ‘fulness of time,’ when the perfect moment came, Christ was born, bringing in the time of redemption. From a Scriptural perspective, most Christians are familiar with God’s plan of salvation and could probably trace important prophecies and fulfillments from the OT and NT. However, when was this perfect moment within history? Why did God choose that specific era for Jesus to be born into?

Here is a historical survey of insight regarding Christ’s birth. It is incredible to observe the world that Jesus was born into, as this time period has some of the most fascinating events and colorful individuals in history.

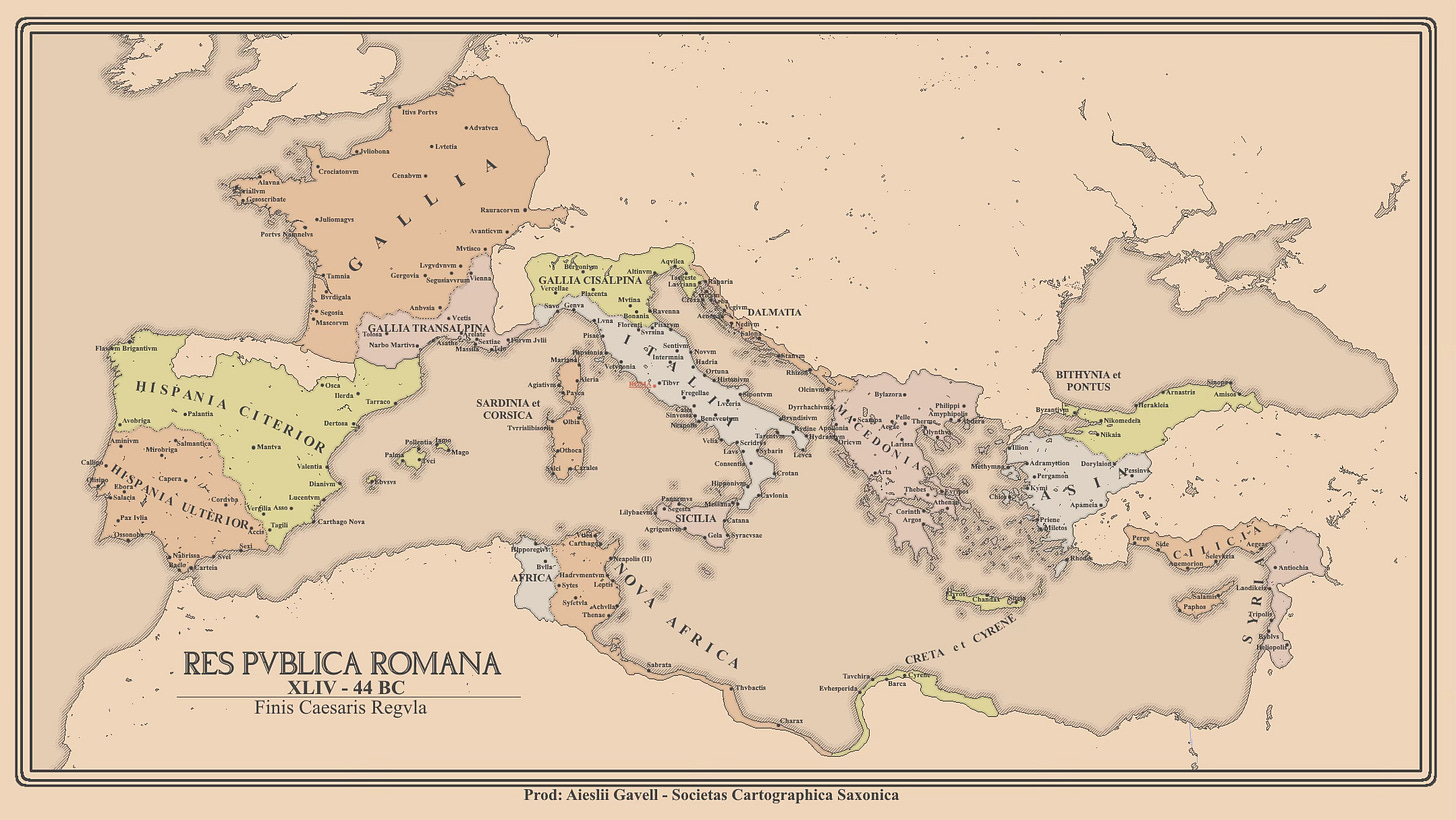

We will start and end in 63 BC. This date is significant for two primary reasons.

The future emperor Augustus was born.

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) conquered Jerusalem and added the kingdom to the Roman Republic’s rule.

Over the last two decades or so, Pompey had become quite the celebrity. He had already held Rome’s highest political office, been praised as Rome’s finest general, and was declared the ‘Alexander of the West’, a title Pompey pridefully adored. His nickname derived from the numerous victories he collected, as he defeated some of Rome’s worst enemies at the time. Another nickname he received as a young man was ‘the butcher.’

Pompey was on his way back to Rome after one of these great victories when he was approached by rival Jewish leaders, both desiring his support. The situation escalated into Pompey besieging Jerusalem and taking the city. But Pompey could not leave Jerusalem until he satisfied his curiosity, so he entered the place few people had gained access to: the Most Holy Place in the Temple. He was surprised to find nothing, no idol or sacred object. The general left respectfully, not removing any of the treasury, and the next day ordered that the sacrifices resume. Judaea retained their Jewish leadership but would come more and more under Roman authority in the coming decades.

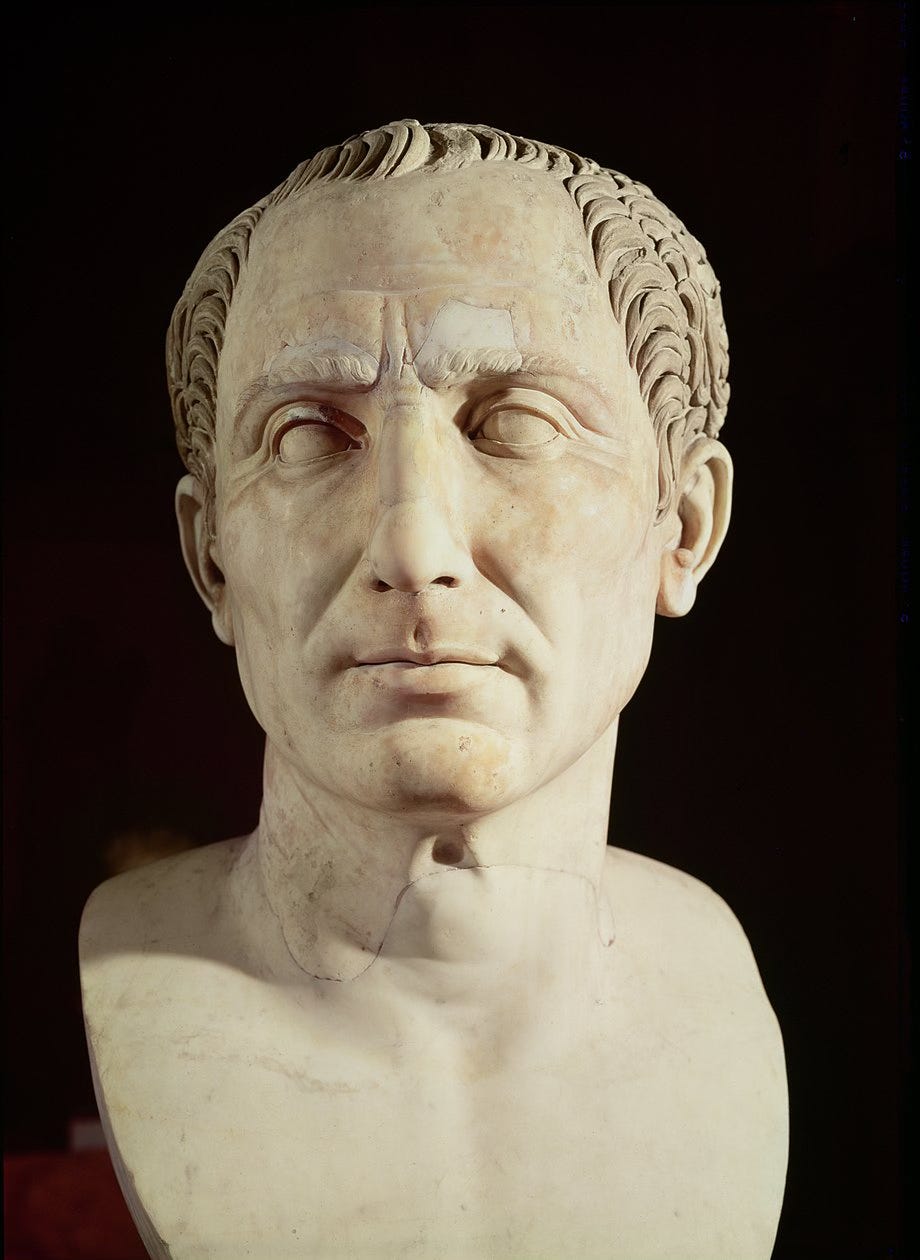

At this time, no Roman was considered to be on Pompey’s level. However, there was one rising star who would become Pompey’s greatest rival. It was said that Pompey would not accept anyone as his equal, but this next man would not accept anyone above him. This younger man was Gaius Julius Cæsar, and he was on his way to the top of Roman politics.

This era of Roman history was before the Empire had emerged. Rome was a republic, but it was in total chaos with multiple civil wars, social turmoil, and slave revolts. A young Julius Cæsar had seen some perilous situations firsthand, including being kidnapped by pirates and held for ransom. Not at all acting like a prisoner, Cæsar told his captors they should have demanded more money for his release, but once released he would return and execute all of them. Cæsar kept his word. Aged just 25, this was an impressive feat and his courage would be a sign of things to come.

Cæsar went through the normal steps of entering the Roman senate, and with great effort, he gained the love of the Roman populace. He was highly ambitious, as were all Romans at this time, but there was something different about Cæsar. Eventually, he won the highest political office in the Roman Republic: he became one of the two consuls for the year 59 BC.

In his year as consul, Cæsar won fame, glory, and many enemies. He was a somewhat uneasy ally with Pompey, but their influence on others led to the passing of many laws which helped various factions in Rome. The people adored Cæsar but some in the uppercases did not. To stay out of reach of his enemies, Cæsar moved to Gaul, modern-day France, to serve as the Roman governor.

Cæsar wrote The Gallic Wars while governor, which can be read today and includes wonderful stories of his battles, explorations, and bravery. He did things that amazed the Romans back home: Cæsar was the first Roman to cross the Rhine into Germany, the first to cross into Britannia (Britain), and he ultimately subjugated Gaul for the Republic. A modern-day equivalent would be if Donald Trump discovered Atlantis, it would be shocking and bring high honor to the discoverer.

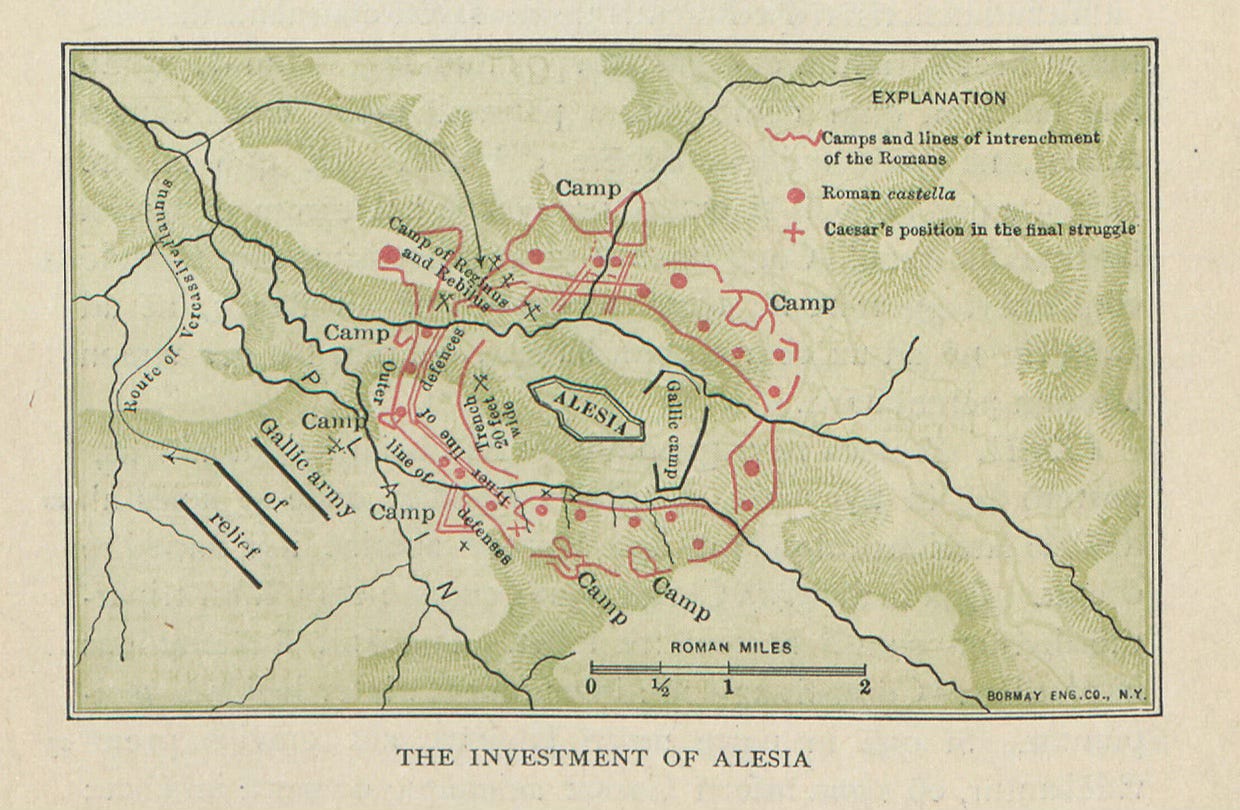

But everything was almost lost in 52 BC. From 58-52 BC, Cæsar had defeated every hostile enemy, Gauls and Germans, but he now faced a clever and determined adversary. Vercingetorix was a tribal leader who amassed a following of tribes that wanted to push the Romans out. Vercingetorix won a few engagements so Cæsar had to take him seriously. It came down to a hill fort called Alesia. The Romans had approximately 45,000 soldiers, while the Gauls had nearly 80,000 in the fort. Cæsar surrounded the fort, but to the Romans’s alarm, enemy reinforcements arrived. There may have been 100,000 Gauls that were coming to Vercingetorix’s aid, which means the Romans were vastly outnumbered. Cæsar had another wall built facing their rear, along with pits, ditches, and traps. Facing the enemy on two fronts, the Romans were in a desperate situation, but their general was not just anyone. He was Gaius Julius Cæsar.

Once the battle began, the enemy targeted the weakest points of the Roman defenses. Cæsar issued orders but eventually saw the danger was mounting and if something was not done to rally the men, all would be lost. Cæsar donned his red cloak, which identified him as the general, and began to ride through the ranks of his soldiers. The soldiers recognized his red cloak, and hearing his encouragement they began to push the Gauls back. With the help of the Roman cavalry, the enemy was driven back and all hope for the rebellion was crushed. Cæsar had won a spectacular victory.

Vercingetorix was surrendered alive to the Romans and was taken to Rome to die as a prisoner. There was still work to be done in Gaul, but the victory at Alesia had defeated a major threat.

As Cæsar’s time as governor was nearing an end, his enemies in the Senate were growing anxious. They did not want him to return to Roman politics, and sought a means to destroy or exile him. Cæsar had been in an unstable alliance with Pompey, not that they hated each other, but they were definitely rivals. Pompey had married Cæsar’s daughter, and it had been a very happy marriage until she died in childbirth. There were no more ties to keep Cæsar and Pompey together.

This is near the time when Cæsar famously crossed the Rubicon River, which was an act of treason because he retained some of his soldiers while entering Rome’s borders. Cæsar’s enemies declared him a traitor, never mind that Pompey had done the same things that Cæsar was being condemned for. Most people involved did not want another civil war, but after a few years of attempted diplomacy, there was no resolution. A truce was almost established, until one senator named Cato, who probably hated Cæsar the most, stood up and broke negotiations to declare war instead of peace.

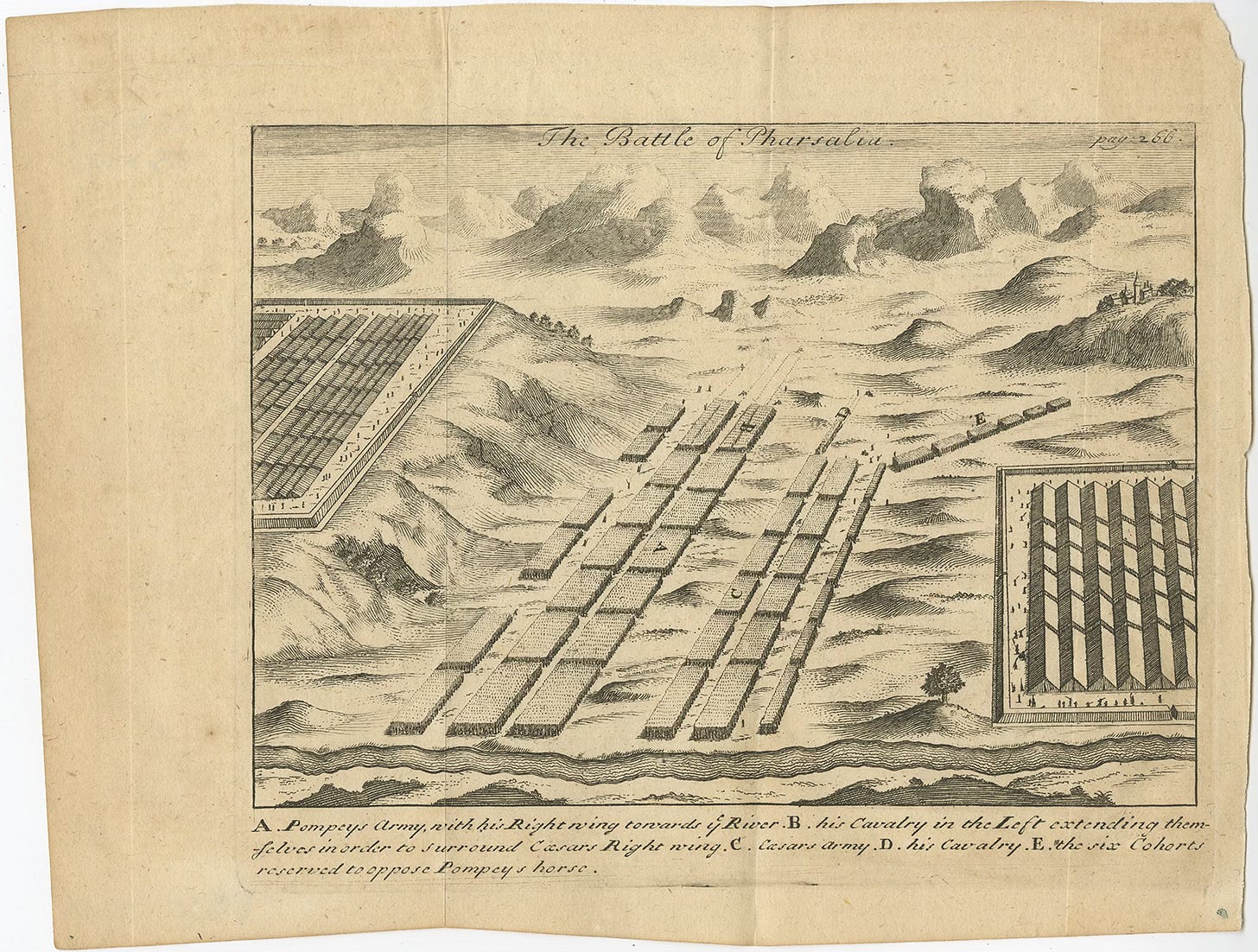

In 48 BC, Cæsar found himself outnumbered again. He had around 22,000 soldiers, facing Pompey’s 42,000. However, this time the enemy was not tribal Gauls, but fellow Romans. The Battle of Pharsalus pitted two of Rome’s greatest generals against each other. Both had won incredible battles and subjugated entire lands for the Republic, but this battle would prove to be decisive — only one could be victorious.

Cæsar risked the battle, his army, and probably his life on a surprise maneuver. Pompey’s infantry advanced but when his cavalry attempted to flank Cæsar’s line, Cæsar’s hidden soldiers attacked and routed Pompey’s cavalry. The end was a total Cæsarean victory.

Julius Cæsar was now the most powerful man in Rome. There was still opposition to deal with, which took Cæsar to Egypt where he discovered that Pompey had been assassinated. Cæsar also met the famous Cleopatra, but was besieged by her brother who sought to drive the Romans away. The Romans were vulnerable, but a man from Judaea came to Cæsar’s rescue, Antipater the Idumaean. Remember Antipater, we will meet his son later.

Let’s pause and reflect on all of these precarious events, there will be more to come, but if any of these circumstances turned out differently, then all of history would have changed dramatically. But God is still in control, even in the chaos of history.

When Cæsar returned to Rome, he showed himself to be different from all the previous generals of his era: he forgave his enemies. Not only did Cæsar receive them back, he appointed them to positions within the Republic. Julius Cæsar is often depicted as a tyrant, but that argument does not totally match the evidence. He made several laws to better the Roman people, but the idea of a tyrant comes from the fact that he passed these laws without consulting the Senate. Because Cæsar had diminished their authority, some Senators began to conspire against him.

March, 44 BC, Cæsar was preparing to leave on a military campaign that would have taken him away from Rome for several years. His enemies had to act quickly. Cæsar was on his way to meet the Senate when he received a note, unfortunately, he did not read it. The note detailed how a group of 50-60 individuals had planned to murder him. On 15 March, 44 BC, Cæsar was stabbed 23 times and died on the floor under a statue of Pompey. The conspirators thought they would be hailed as heroes, instead, the streets were silent. Later, a mob was roused at Cæsar’s funeral, which prompted the conspirators to flee for their lives.

Enter Octavius Thurinus, Cæsar’s great-nephew. He was only 18 when Cæsar was assassinated, a young man about to enter the dangerous world of Roman politics. His family begged him to stay away from Rome, but Octavius would not be hindered. Shortly thereafter, he discovered he was the primary heir of Cæsar’s will. This means that Octavius received Cæsar’s name, money, and loyalty of his soldiers. Historians normally refer to him as Octavian at this point in his life, but he never called himself that. Instead, he called himself Cæsar. To avoid confusion, we will call him Young Cæsar.

To summarize, Young Cæsar teamed up with Mark Antony, a former officer under Julius Cæsar. Together they hunted down and defeated Julius Cæsar’s assassins. However, over the next decade strong division brought on another civil war— the final civil war of this era. Young Cæsar stood on one side, while Mark Antony and Cleopatra stood on the other.

In 31 BC, a sea battle will determine the fate of Rome and the ancient world. Antony and Cleopatra were surrounded, with disease running throughout their camp and soldiers deserting to Young Cæsar. They had to do something desperate to break through the blockade. The Battle of Actium began with Antony’s fleet advancing, but when he saw Cleopatra’s ship, which held the treasury, fleeing the battle, he chased after her. The battle was a complete victory for Young Cæsar. Both Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide in Egypt.

As his great-uncle before him, Young Cæsar found himself at the top of the Roman world. A war-lord with no one to stand up to him. However, the people were ‘bewitched with peace’ as one ancient historian put it. After 100 years of civil wars, the Romans were happy to have the madness end. Young Cæsar ushered in the Pax Romana, or Roman peace, across the ancient world. A fantastic administrator, he traveled extensively and was hailed as a hero for bringing order and safety to the Republic. More titles and names were added to Young Cæsar, including Imperator (literally victorious general, where our word emperor comes from), and Pater Patriae (father of his country). However, history famously remembers him by another name, Augustus (revered or holy one). This is IMPERATOR CAESAR DIVI FILIUS AUGUSTUS PRINCEPS PATER PATRIAE. He was Rome’s first and, almost certainly, greatest emperor.

Our story began in 63 BC, when Pompey added Judaea to Roman power and when Augustus was born. These two events were significant for the birth of Jesus, as Judaea was under Roman control, which allowed a later leader to declare a tax across the Roman world that the Judeans had to obey.

Luke 2:1 And it came to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.

Luke 2:4-5 And Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judaea, unto the city of David, which is called Bethlehem; (because he was of the house and lineage of David:) To be taxed with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child.

One crucial element to Roman order required client nations to pay taxes. It was one of these taxations that Luke recorded as the reason why Joseph left his home in Nazareth and traveled south to Bethlehem. Without the census-tax, he would have had no reason to journey to Bethlehem. It just so happened at the same time, the perfect time, that Mary was nearing the end of her pregnancy.

Now, think about how God used all of these events to bring about the greatest birth in all of history. If Julius Cæsar died earlier than he did then Young Cæsar would not have risen to prominence when he did. Also, what about Julius Cæsar in Egypt? Antipater saved him. The son of Antipater enters our story right at Jesus’ birth,

Matthew 2:1 Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king…

Both Herod and Augustus reached their powerful positions, in part, because they built on what their relatives had accomplished, and both played important roles in the events surrounding Christ’s birth.

My hope is that when you hear someone read Luke 2 this season and you hear Augustus’s name, I hope you think of God’s hand in history. Yes, we know God worked within the Bible events, but He also worked in events not recorded in Scripture. Christ’s birth was at the perfect historical moment, it did not happen randomly or in a vacuum. Today, we celebrate and gain encouragement from remembering His birth and sacrifice, but let us not forget—He is coming back one day. Christ was not born just simply to die, but He was born to reconcile the world back unto Himself and one day rule on David’s throne as the King. If God worked in history to bring about Christ’s birth, so too is He working in history to bring about His return.

Merry Christmas!

Recommended resources for ancient history:

Adrian Goldsworthy — by far my favorite ancient historian

Hillsdale Dialogues — a podcast where Larry Arnn walks through important ideas and people from history

The Landmark History series— primary sources with maps and commentary. Very easy and fun reads. https://a.co/d/hrGwuAj

Great historians— Victor Davis Hanson, Paul Rahe, and Barry Strauss

Check out these blogs if you enjoyed mine,